An award-winning writer, columnist, critic, academic, broadcaster, public intellectual and former political candidate. Dr Elizabeth Farrelly is trained in architecture and philosophy.

An award-winning writer, columnist, critic, academic, broadcaster, public intellectual and former political candidate. Dr Elizabeth Farrelly is trained in architecture and philosophy.

Elizabeth trained in architecture and philosophy, practiced in London and Bristol and holds a PhD in urbanism from the University of Sydney, where she is also a former Adjunct Associate Professor.

As an independent Sydney City Councillor (1991-95), Elizabeth initiated Sydney’s first heritage and laneway protection policies, and was inaugural chair of the Australia Award for Urban Design (1998). She was also Manager Special Projects at the City of Sydney during the Olympic preparations (1998-2000) and is an award-winning writer and published author.

Elizabeth holds a number of national and international writing awards. As Assistant Editor of The Architectural Review (London) Elizabeth edited the August 1986 special issue ‘The New Spirit’, which won the Paris-based CICA award for architectural criticism. Her other awards including the Pascall Prize, the Walter Burley Griffin Award, the Adrian Ashton Award and the Marion Mahony Griffin Award.

An articulate, interesting and engaging speaker, Elizabeth Farrelly is skilled at making complex issues accessible to diverse audiences both in Australia and overseas.

Australia

Australia

France

France

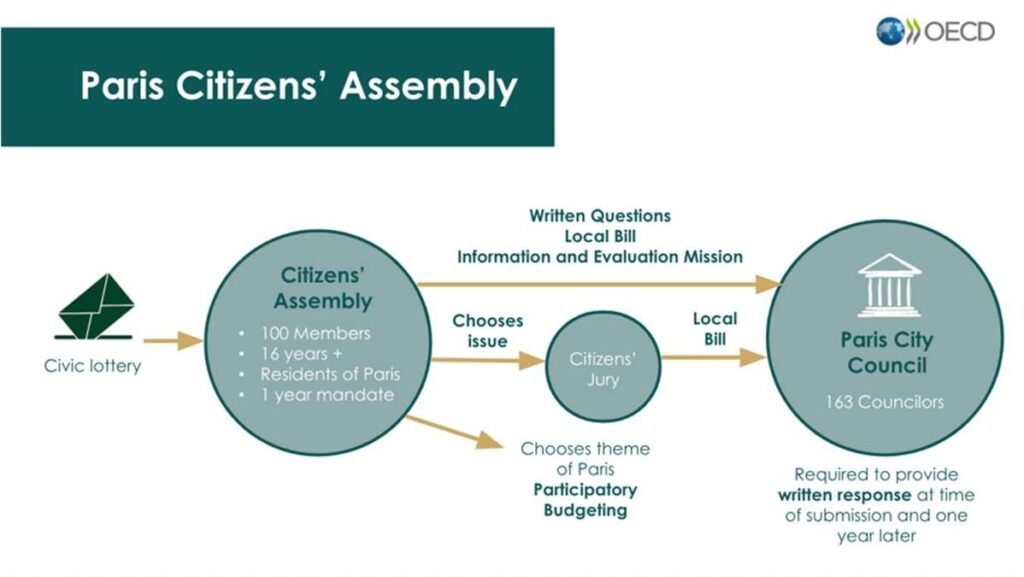

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development)

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development)

Emma Fletcher is Co-CEO of Australia’s leading deliberative democracy company – democracyCo. In this role she designs, and project manages large and complex engagement projects.

Emma Fletcher is Co-CEO of Australia’s leading deliberative democracy company – democracyCo. In this role she designs, and project manages large and complex engagement projects.

An award-winning writer, columnist, critic, academic, broadcaster, public intellectual and former political candidate. Dr Elizabeth Farrelly is trained in architecture and philosophy.

An award-winning writer, columnist, critic, academic, broadcaster, public intellectual and former political candidate. Dr Elizabeth Farrelly is trained in architecture and philosophy. Nicholas Gruen, CEO of Lateral Economics is a widely published policy economist, entrepreneur and commentator. He has advised Cabinet Ministers, sat on Australia’s Productivity Commission and founded Lateral Economics and Peach Financial.

Nicholas Gruen, CEO of Lateral Economics is a widely published policy economist, entrepreneur and commentator. He has advised Cabinet Ministers, sat on Australia’s Productivity Commission and founded Lateral Economics and Peach Financial.